lessons from the Monty Hall Problem

NOTE – you’ll need to be familiar with the Monty Hall Problem to get anything out of this – if you aren’t – then leave – by any door you choose

the Monty Hall Problem isn’t a trivial exercise – there are life lessons to be teased out of it

—

when i first read the problem – i counted 2 unopened doors at the end – so i guessed 50-50 – but Marilyn vos Savant said otherwise – so i assumed she was right – it was that easy and painless for me – after all – puzzles are supposed to be tricky & baffling – and i had often been defeated by them – so i didn’t invest my ego in my first impression – and i surrendered to Marilyn’s expertise

strangely enuf – many laymen of my caliber seemed to have heavily invested their egos in their answer – like me – they concluded the answer could only be 50-50 – but unlike me – they clung to their first impression

they probably took comfort in the many professional mathematicians who also came to the same conclusion – shouldn’t they know more than Marilyn – many began by snidely contradicting her – pointing to alphabets behind their names – some of those with integrity ended by writing what must have been a painful concession

>> try to back off when feeling the need to be right – be worried when sure you’re 100% right – that’s not being humble – it’s being practical – it allows us to move on with minimal bruising if proven wrong

the first step to finding a solution to a puzzle is to find a clear statement of the problem – for me – this means visualizing it

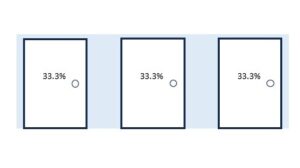

here’s how i first perceived the setup

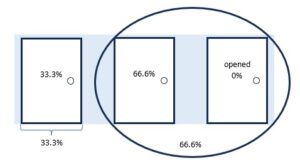

it asks a question – if one of those encircled doors is revealed to be prizeless – does the probability of that revealed door get distributed to the other door within the circle

it took awhile for this to occur to me – but when i used that image to help a coworker understand the problem – his quick grasp of how it leads directly to the solution – convinced me that it was apropos

those that didn’t manually or mentally draw a circle around the doors after a prizeless door was opened – saw 2 unopened doors – which looked like the oh-so-familiar 50-50 situation – but that was the extent of their thinking process – they didn’t go on and try to prove it

probably cuz many didn’t know how to prove it

>> find the right statement of the problem – try different viewpoints – until one directs you to an answer – then double check yourself – stay away from thinking it is settled

when i came up with the circled doors visualization – i knew i had to prove its implication – the implication that the probability of the revealed door transfers to the remaining door within the circle – but i didn’t know how to prove it – i lacked the mathematical tools needed

in time – i realized that probabilities need to match up with what happens in reality – if math results differ from real world results – then the math is wrong

so i searched for a real world proof instead

it turns out that Marilyn had already pointed the way – after giving up on explaining her reasoning to her skeptics – she resorted to advising people to play out the game from beginning to end – more than once

she knew that ALL the steps had to be performed in order to get an accurate result – while many people – even professionals – saw 2 unopened doors at the end – and thought the initial steps of the puzzle were irrelevant

she also knew that playing the game only once doesn’t result in probabilities to rely on for future challenges – that would be like flipping a coin once – and if it came up heads – assume that flipping that coin will result in heads forevermore – but you know from a lifetime of coin flips – that the probability for turning up heads are 1 out of 2 – and the probability for tails are 1 out of 2

Marilyn asked math teachers to have their students play out the game – so they could add up the number of wins for those who stayed – and the number of wins for those who switched – and send her the results

the results gathered by Marilyn were – <drumroll> – players who stayed won 1 out of 3 times – players who switched won 2 out of 3 times

the results were unambiguously not 50-50

i on the other hand – didn’t want to play out the game the number of times it would take to produce reasonable probabilities – so i created a simulation in an Excel spreadsheet – using its random number generator – it produced 100 results when started – and another hundred each time i hit the refresh key – i had an accumulator which added up the results – and as i watched it – the results got closer and closer to winning 1/3 of the time when staying – and 2/3 when switching – QED

>> perhaps the important lesson from the Monty Hall Problem is to follow thru – play ALL the steps – don’t truncate them – and if seeking probabilities – don’t rely on a single play

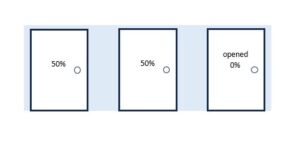

to be fair – many of us have 50-50 scenarios burned into our brains – we shouldn’t be surprised at the knee jerk reaction that brings many of us to see 2 remaining doors after Monty has revealed a prizeless door – and conclude that the probabilities are 50-50

but the Monty Hall Problem is NOT the same a flipping a coin – it shouldn’t be treated the same – the few extra steps before there are 2 remaining doors to pick from – make all the difference

suppose the game did not start with the player selecting a door – instead Monty first reveals a prizeless door – then the player selects from the two remaining doors – probabilities calculated at that point would assign each door a 1 out of 2 chance – this simpler situation was how i first saw it – and many others did too – including pro mathematicians

however – in the Monty Hall Problem – the player selects first – Monty opens a door – and then the player chooses between staying or switching – the analysis needs to take those steps into account

once the player has selected (step 1) – probability assigns each door a 1 out of 3 chance – then once Monty reveals a prizeless door (step 2) – Monty has FORCED the player who switches (step 3b) – to choose the door with the prize – IF – this happens during the 2 out of 3 times the prize sits behind one of those 2 doors – that door may be the second door or the third door – whichever – that door is guaranteed to have the prize those 2 out of 3 times – whereas – during the alternate 1 out of 3 times – the prize will be behind the door first selected

it’s the player selecting a door immediately at the start – that gives that door its 1/3 probability – and the 2 others a combined 2/3 probability

it’s the opening of one of those 2 unselected doors (a prizeless one) – that changes the probability of the unselected closed door – from 1/3 to 2/3

this situation is very unintuitive – we don’t encounter this situation very much in our lives – that’s why it’s difficult to fathom

>> beware of what you think you know – of seeing only what is familiar – double check – don’t err on the side of laziness

there’s a strange moment when playing the Monty Hall game – if the player’s first pick is the door with the prize – Monty will open a prizeless door – and at that moment – probability insists the player switch AWAY from the door with the prize – to a door without it

probability doesn’t guarantee the player will win when following its advice – in the above situation – he will definitely lose

but without prescience power – choosing to stay is based on anything but logic – it is based on intuition – on a hunch – these are all hallucinations – – fortunately for the player who switches & loses while playing this game – there is no penalty for losing those 1 out of 3 instances – the player will go home without the prize he never had – – the player who plays a hunch and stays – will go home with a prize he should have lost 2 out of 3 times – he can indeed celebrate for “beating the odds”

however – if the penalty is more severe – such as a life or death decision – and the decision maker wants to go with a hunch – and ignore what probability advises – that is a more ominous moment – while there seems little difference between 1/3 and 2/3 – the latter is twice as good as the former

whichever choice players makes – players should prepare themselves for their choice being the losing one

the only guaranteed win is when the probability is 100% – but even then – the result may turn out differently – probabilities are calculated by humans – and calculation errors might have been made

>> probability advises – but doesn’t guarantee outcomes – probabilities just tell us how surprised to be – still it is life’s best guide for now – better than intuition – however – calculating probabilities can be difficult – as demonstrated by the Monty Hall Problem